Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

In recent years, UZH has invested a lot of resources in establishing an open-access publishing culture. This issue has acquired strategic importance ever since the enactment of the Open Science Policy in 2021, if not before then. Where do we stand today?

Elisabeth Stark: We have raised awareness about open science at UZH enormously over the last few years. A lot has been achieved in certain areas such as open access to publications. We have not progressed as far yet in other domains such as open research data, open source and open code, but that has to do, in part, with the fact that they are newer issues that pose challenges of greater complexity depending on the subject area and type of data concerned.

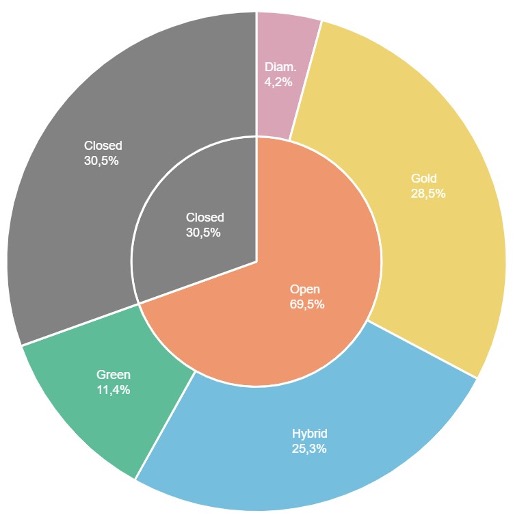

Andrea Malits: I can confirm that we have made great progress in the area of open access and can deem it a success story: the share of open-access publications has continually increased in recent years to now almost 70% at UZH and throughout Switzerland as well, by the way. The Read & Publish deals that we arrange – in part for all of Switzerland and in part exclusively for UZH – have contributed considerably to the success story.

Christian Schwarzenegger: The publishing world has undergone a dramatic change in recent years. When the national open access strategy was adopted in 2017, most publications were locked behind paywalls, and researchers reacted to the new standards and guidelines in a state of near shock. Today UZH achieves an open-access publication ratio of a good 70%, albeit in a number of different ways. This accomplishment is the result of the broad promotion of open-access publishing through the university policy, the Open Science Office, the Open Science delegates, and the services provided by the University Library. In a span of just a few years, we have created a constructive, future-minded open access spirit at UZH. In order to get to 100% open access, we need additional measures such as alternative publishing models and the enactment of a secondary publication right at the national level, which is also being called for by the revised open access strategy adopted by Swissuniversities and the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Why is a secondary publication right important?

Andrea Malits: At the moment, it so happens that researchers in some cases grant sweeping usage rights to their scientific papers exclusively to publishing houses. That hinders the archiving of publications in institutional repositories like ZORA at UZH, for example. The right to a second publication, like the one that already exists in other European countries, would solve this problem.

Open science, with its open access to publications, programs and research data, requires a cultural change. Do researchers at UZH support that?

Andrea Malits: I see a change in culture mainly among the younger generation of researchers. To them, it’s self-evident that access to their publications must be open and that they – not the publishing houses – must hold the rights to their publications. After all, it’s their research and their findings that they worked hard to produce with a lot of dedication, and they would like to retain control over their work. A change has taken place here that makes me feel very optimistic, but that’s also connected with the university’s aspiration to provide good services in these areas.

Elisabeth Stark: Researchers have clearly understood by now that open science isn’t merely a minor matter, but instead is a central issue and a core competence that ultimately serves their own best interests.

Christian Schwarzenegger: That’s true, the underlying idea of open science and of open access in particular makes obvious sense to researchers. All of them want their research papers and academic work to be disseminated and read as widely as possible. We don’t have a problem at this level.

But we do in other areas?

Christian Schwarzenegger: Andrea Malits touched on there being a need for support measures on the part of the university. Although the new publishing channels are welcomed and appreciated, researchers don’t have time to concern themselves with them in depth. Instead, they are asking us to arrange an efficient publication service so that they can publish their papers in the best possible setting without much fuss and expense. I’m not talking here about peer reviewing, which of course is up to researchers themselves to arrange, but am referring to the publishing process in the narrower sense.

Does this mean more overhead and service provision for the university than before?

Christian Schwarzenegger: Yes, it entails much more overhead and effort. On the one hand, we are trying in an international context to come up with a publishing-as-a-service model together with major scientific publishing houses like Elsevier, Wiley and Springer. All scientific and academic publications originating from Switzerland are to be open access. Their databases are to be made searchable and analyzable via artificial intelligence solutions, and terms of use are to guarantee the widest possible reuse of their contents (CC BY license). On the other hand, long-form publications and “local” journals in German, French and Italian are also to be transformed into open-access formats. We can’t leave it up to researchers themselves to work out and negotiate solutions of that kind.

Elisabeth Stark: Of course there is also quite a number of researchers who act as editors of journals. Convincing them of the necessity and benefits of open-access publishing is often a part of our job. However, open science also has altered the publishing landscape insofar as many a publishing house has discovered a new business model in the extra publication fees for open access, the effects of which are counterproductive. Moreover, publishing houses have a penchant for founding additional new publication series and journals for which they dangle lucrative honorariums to lure researchers as reviewers and editors. The quantity of publications increases and so do the costs in the entire system along with that while the quality issue often lags behind.

We have expanded open science services at the University Library. Those services provide researchers with practical support in the publishing process and in the management of research data.

In the wake of the successful establishment of open science at UZH, the second phase – consolidation – is now beginning. What are the specifics of the planning for the near future?

Christian Schwarzenegger: Open science resides at the intersection between research and services that are usually provided by libraries. So, in the first phase, we accordingly incorporated the Open Science Office and the delegates in the Office of the Vice President Research at first in order to instill this spirit throughout the institution as quickly as possible.

In the meantime, we have expanded open science services at the University Library. Those services provide researchers with practical support in the publishing process and in the management of research data through, for example, the Data Stewards Network, which is currently being built up. Now we are broadening the job performed by Andrea Malits’s office with new tasks previously rendered by the Open Science Office. Next year, for instance, we intend to convene an extended task force of open science delegates to further develop the implementation of open science. This means that the consolidation and sustained further development of open science will happen at the University Library, which reports to my Office of the Vice President Faculty Affairs and Scientific Information.

Elisabeth Stark: This transfer to the University Library was the result of an intensive strategic process that we conducted in recent months across two management areas of the university. I expressly applaud this outcome. Looking ahead to the future, it is right and sensible that there will be an institutional contact point for open science at the University Library. As the Vice President Research, I and my team will of course continue to be closely involved.

As mentioned previously, a new open science working group is planned as part of the reorganization. What is its mission?

Andrea Malits: The working group will convene representatives from all faculties that are familiar with open science through their field of work. It will bring a lot of know-how together that we can funnel back to faculties and departments across the board. I envision the working group setting priorities and devising implementation scenarios for the main open access, open data and open code issues. We can sustainably further develop open science at UZH through this stepped-up cooperation with researchers and drivers of open science.

Will the area of open science be strengthened by consolidating it in the University Library?

Christian Schwarzenegger: It most certainly will. We are concentrating and intensifying our efforts and have also been awarded more funding for that under the university’s development and financial plan.

UZH also has successfully acquired external funding for open science from swissuniversities – almost six million francs (as of July 24) to be exact. A closing event for the projects funded by swissuniversities will be held on 18 November. What distinguishes those projects, and where is UZH particularly strong?

Andrea Malits: The projects originated from an array of different subject areas ranging from chemistry and botany to linguistics and biomedicine. What distinguishes the projects is their breadth spanning all faculties. Seldom have I perceived UZH so vividly as a comprehensive university.

Christian Schwarzenegger: Our aim with the event is to pay tribute to the projects for which we obtained funds for the 2021–2024 funding period and to increase their visibility. Given the federal government’s efforts to cut spending, at the moment it is still unclear how exactly calls for applications for grants from swissuniversities for the 2025–2028 period will be continued in detail.

Elisabeth Stark: Allow me to add that the successful fundraising also had to do with the excellent preparation of the applications and the follow-up support provided by Christian Schwarzenegger’s office. People didn’t submit applications willy-nilly. Rather, the projects were evaluated and coordinated internally.

Researchers have clearly understood by now that open science isn’t merely a minor matter, but instead is a central issue and a core competence that ultimately serves their own best interests.

Swissuniversities and the Swiss National Science Foundation set the open science agenda at the national level. Next year marks the start of phase II there as well: the updated national open-access strategy is striving for a switch to 100% open access by 2032 at the latest. Can UZH reach that goal?

Christian Schwarzenegger: I’m optimistic – enthusiasm and a get-up-and-go attitude toward open science certainly exist. From the standpoint of the Executive Board of the University, it’s important to make the switch in a way that’s sustainably fundable. The revised national strategy also explicitly stipulates this. Specifically, this means that we cannot pay the big publishing houses limitless amounts of money for open access. There is a charged relationship here because profit-oriented publishing houses try to exploit dependence. They actually even reinforce dependence by constantly developing and providing new analytical tools and supplemental services.

Have the Read & Publish deals with the big publishing houses that enable researchers to publish open-access articles for free in fact come under criticism again and again because the publishing houses earn high profits off them?

Christian Schwarzenegger: In the past, the major publishing houses exploited the higher price level in Switzerland, similar to the case with pharmaceuticals. Germany now has been able to reduce the open-access cost per article through hard-nosed negotiation, and I think that we can benefit from that in our ongoing negotiations. I’m confident that our deals will lower the cost per article. However, the overall cost trend also depends on the total quantity of publications, which continues to increase.

To reduce dependence on commercial scientific publishers, universities have also begun to develop their own publishing channels, such as diamond open access. What is UZH doing on that front?

Christian Schwarzenegger: A few years ago, we set up the HOPE publishing platform at UZH (HOPE stands for Hauptbibliothek (Main Library) Open Publishing Environment). The platform is a technical service provided for publishers at UZH so that they don’t have to fuss with hosting and the associated workflows. Approximately 20 open-access journals are available on HOPE by now, and our strategy is to continue to vigorously promote diamond open access. It is a vital alternative to the big publishing houses.

Elisabeth Stark: It makes sense in any case to set up proprietary publishing channels. In the field of linguistics there are good examples demonstrating that diamond open access can work. The journal Glossa, for instance, was hatched from the Elsevier journal Lingua when the entire editorial staff resigned from Lingua and founded a new diamond open access journal under the new name. The field of linguistics also has a well-functioning diamond open access scholarly publishing house called Language Science Press.

Don’t proprietary publishing houses operated by universities simply mean a shifting of costs, with the money going to the universities’ own outfits instead of to the big publishing houses?

Elisabeth Stark: The publishing work gets shifted to the universities, but the costs are much lower on the whole.

Andrea Malits: The Glossa example is an interesting case. If it is possible to take over established journals from major publishing houses, that’s a sensible option. On the one hand, that renders developmental work unnecessary because the journal is already well-known, and on the other hand, we have the publication channels under our own control, as is the case with diamond open access. This flipping model ought to be employed more often.

I see a change in culture mainly among the younger generation of researchers. To them, it’s self-evident that access to their publications must be open.

What about the area of open research data? Are there any specific plans?

Christian Schwarzenegger: The projects for which we acquired funding from swissuniversities have enabled us to generate a lot of momentum regarding practices in dealing with research data, and we continue to pursue this issue. At the same time, UZH needs more capacity for preparing and editing data – a greater effort is needed here.

At the national level, efforts are underway to develop solutions across all of Switzerland that establish data repositories on specific subject areas at certain institutions that can be used by all researchers. That’s not all that easy an undertaking, though, in our federalist system with universities that are financed differently. But we have already notched some successes with SWISSUbase and the cooperation between UZH’s linguistics technology platform LiRI and LaRS, the Language Repository of Switzerland.

Elisabeth Stark: Another aspect is the dramatically growing need for data storage capacity – this is practically a law of nature in data-driven research, and it’s gaining a lot of importance right now. The data generated by the Center for Microscopy and Image Analysis technology platform alone is stretching our capacity to its limits. Moreover, the subject of open research data is very complex because there are different types of data that present different challenges with regard to confidentiality, accessibility and storage. Highly sensitive clinical patient data has to be managed differently than historical or biological data. Unfortunately, the boundaries here are still being drawn for each individual subject area instead of seeking interdisciplinary solutions for each same type of data.

Aren’t there plans for a European cloud service that could alleviate the capacity problem?

Elisabeth Stark: The European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) is in the development stage and offers us connectivity in principle. The Swiss National Science Foundation is currently investigating to what extent this service could meet our needs. In the life sciences sector, a European network called Elixir already exists for sharing and analyzing data.

Andrea Malits: With SWISSUbase, we are able to participate in a technologically focused project as a partner to the EOSC and contribute use cases on utilizing sensitive data. The open science cloud is pursuing an interesting approach to combining data traceability with appropriate editing tools. However, the data itself stays in the countries where it was produced, in part often for legal reasons, but researchers can receive authorization to use it. The EOSC thus does not solve the data storage and storage capacity problem.

Elisabeth Stark: At University Medicine Zurich, we have created a Biomedical Informatics Platform (BMIP) on a smaller scale involving two universities and four hospitals to promote data-driven approaches to medicine. The data stays in the hospitals, but can be used by researchers under certain clearly defined conditions.

In order to get to 100% open access, we need additional measures such as alternative publishing models and the enactment of a secondary publication right at the national level.

Returning to the initial question, UZH, as Switzerland’s largest university, is a key pacesetter for open science. A lot has already been achieved. By when will UZH reach the goals set by the national strategy?

Christian Schwarzenegger: We are well underway thanks in no small part to our Open Science Policy, which we adopted before others did and which gave us the necessary push. How quickly we reach the specified targets depends essentially also on the infrastructure for editing and publishing research data at UZH and at the national level. We need to step up investment in shared infrastructures.

Elisabeth Stark: With regard to open access, I’m confident that we will reach the goals set out in the national strategy, meaning that we will be able to assure universal open access to our publications at the start of the 2030s. Open science is an important issue for both of our vice president offices. We therefore will continue to work together on reaching these objectives.