Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

From fantastic animals to wild creatures and dark monsters; from expansive, brilliant paintings in bold, vehement brushstrokes to ceramic sculptures and dynamic ink drawings; from tiny etchings and illustrations to woodcuts and graphics: Danish artist Asger Jorn (1914-1973) must have been a true berserker, for his oeuvre comprises an almost immeasurable variety of artistic forms. In addition to his extensive pictorial works, he also created an immense body of writing in the form of books, articles, manifestos and essays.

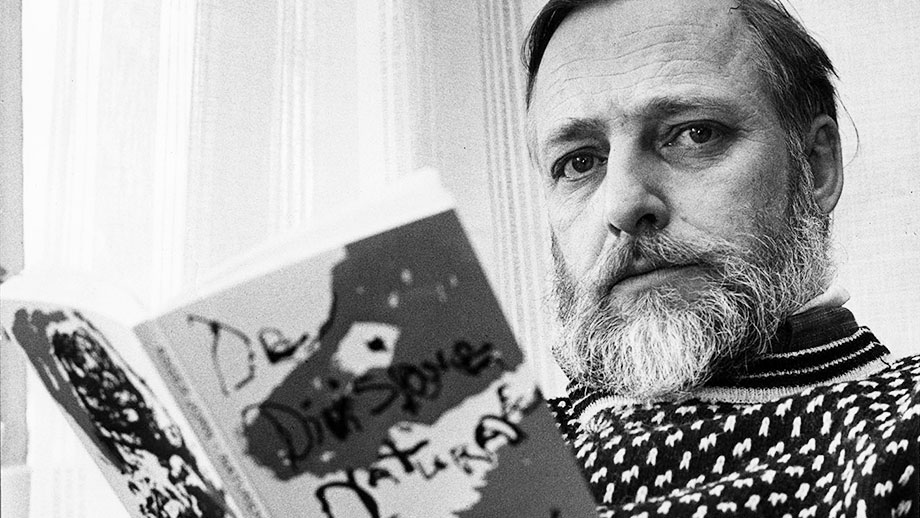

Up till now, Asger Jorn has been known principally for his expressionist paintings filled with weird and wonderful figures often reminiscent of Nordic mythology. However, the full extent of his artistic range, including his aesthetic reflections, has by no means been fully discovered. Eager to redress this situation is Klaus Müller-Wille, professor of Nordic philology. In a broad study that lies close to his heart, the researcher – who studied art history as a minor – aims to reveal the true diversity of this glittering artist. Müller-Wille says that he is still overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of material each time he delves into Denmark's museums and archives to explore Jorn's world.

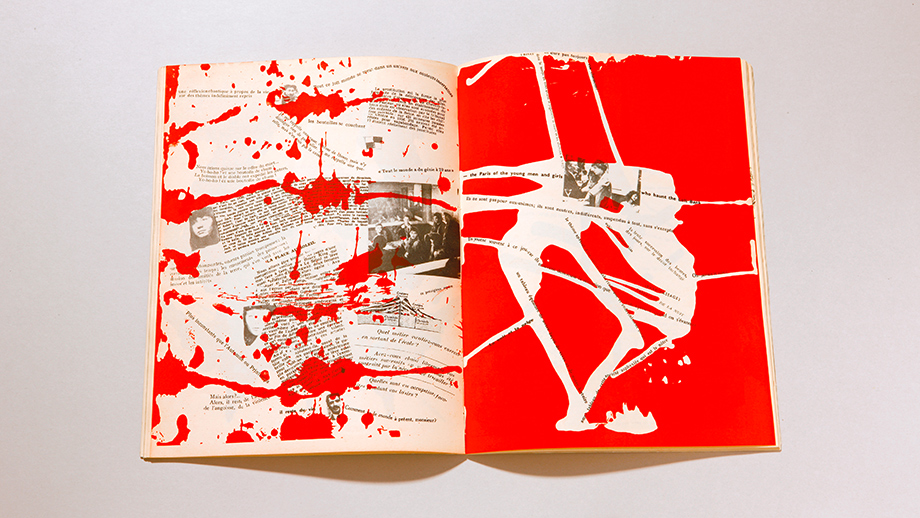

Klaus Müller-Wille is particularly fascinated by Jorn's book art – an artform that ingeniously demonstrates Jorn's reflections on artistic aesthetics and language theory. Indeed, the images in the books give him itchy fingers. How wonderful it would be to touch them! What a haptic experience! The cover of Fin de Copenhague – a book produced within 24 hours in 1957 with colleague Guy Debord – consists purely of words in relief. Made of cardboard and lined with felt, the cover is punched with the text of ads from the Illum department store published in a Danish daily newspaper. The book exposes how Copenhagen was marketed as a tourist destination. In terms of production, the book was an artistic experiment: Jorn and Debord, who later founded the artists' group Situationist International, collected a large pile of newspapers and magazines and made 32 collages consisting of Danish, English, French and German advertisements, marketing logos, comic cut-outs and promotional images, which they then splattered, smeared and smudged with paint.

They took words that had already been used, partially recycled them, and added old text segments, letters of the alphabet, and pre-existing material to create new references. Known as "détournement", which can be translated as misappropriation, distortion, theft or recoding, this practice was popular with the Situationist Internationalists. This grouping of left-wing, avant-garde artistic rebels – and precursors of the '68 movement – attacked the bourgeoisie and capitalism with unannounced public interventions, street actions, political flyers, graffiti and other disruptive actions. .

Asger Jorn was a man who pulled many strings. Today, we would call it networking, says Klaus Müller-Wille. The artist was highly engaged and socially active, bringing artists from different countries into contact. Müller-Wille has discovered valuable correspondence from Denmark's archives, including letters written by Jorn in all kinds of languages – besides Danish and English, also an adventurous Italian and an archaic German.

Jorn's predilection for book art was evident early on. Klaus Müller-Wille presents the beautiful illustrations the artist produced to poems by Genja Katz Rajchmann, published in 1939 under the title Pigen i Ilden (The Girl in the Fire), where circles and areas of color float above, beside and in the text. "Visual art and writing are the same. An image is written, and writing is imagery," writes Asger Jorn in the 1944 essay Prophetic Harps. For Jorn, writing has a physical quality, Müller-Wille explains, and this is the core of his reflection on language theory – which is so intriguing. Writing consists of physical words. The sensory experience of the text – typography, paper, layout – all inform the reading and impact the meaning. The material quality of the book has a dynamic of its own, just as it is with painting, when the colors don't always do what the artist intended, explains Müller-Wille.

Asger Jorn was also instrumental in the design of the bulletins published by the CoBrA Group. Klaus Müller-Wille discovered Jorn when he was asked to give a lecture on the artists' movement at the Université Strasbourg. The group around Asger Jorn and writer Christian Dotremont was aiming to promote smaller capitals as avant-garde centers (CoBrA is an acronym for Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam) and were pushing for more natural, spontaneous, primitive forms of art.

It was there that Müller-Wille noticed Asger Jorn. He was astonished by the intellectual force emanating from this abundance of work by an artist whom he, like most people, had always known simply as a painter. Müller-Wille was particularly fascinated by Jorn's aesthetic writings. In Held og hasard, for instance, he applies the collage technique to his own texts, cutting them up and gluing them back together, in order to both demonstrate and deconstruct his reflections and reasonings.

The philologist refers with a smile to another book ambiguously entitled La langue verte et la cuite, which Jorn published with Noël Arnaud in 1968. La langue means both "language" and "tongue". In fact, Jorn's book is teeming with painted images of tongues sticking out, including the famous picture of Albert Einstein, as well as anonymous tongue photos, tongue paintings, and numerous illustrations of tongue monsters engraved into the facades of Gothic churches. The book is an ironic persiflage of structuralism; with its title alluding to Mythologica I: Le Cru et le Cuit, (The Raw and the Cooked), now an academic classic by French structuralist and anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jorn's work comprises a series of reflections on language play and language theory, served in the form of culinary courses – hence the subtitle: Etude gastrophonique sur la marmythologie musiculinaire.

In it, Jorn criticizes the concept of structuralism, which conceives of language as an abstract, closed sign system, thereby ignoring the physical and sensory aspects of writing. His text collection is peppered with puns and wordplay. Even reading the table of contents is a pleasure: a starter may come in the form of a "sermon fumé" – a smoked sermon – or a "pathétique surgelée" – frozen pathos. After this, a "thèse de veau à la vinaigrette", a veal head thesis, may be served and for dessert a "tarte de rigolade", a slapstick pie. Readers find themselves licking their lips for more. Fortunately, Klaus Müller-Wille's research project, due to be published in a monograph, will soon be serving up more visual and reading delicacies à la Jorn. Enjoy!