Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

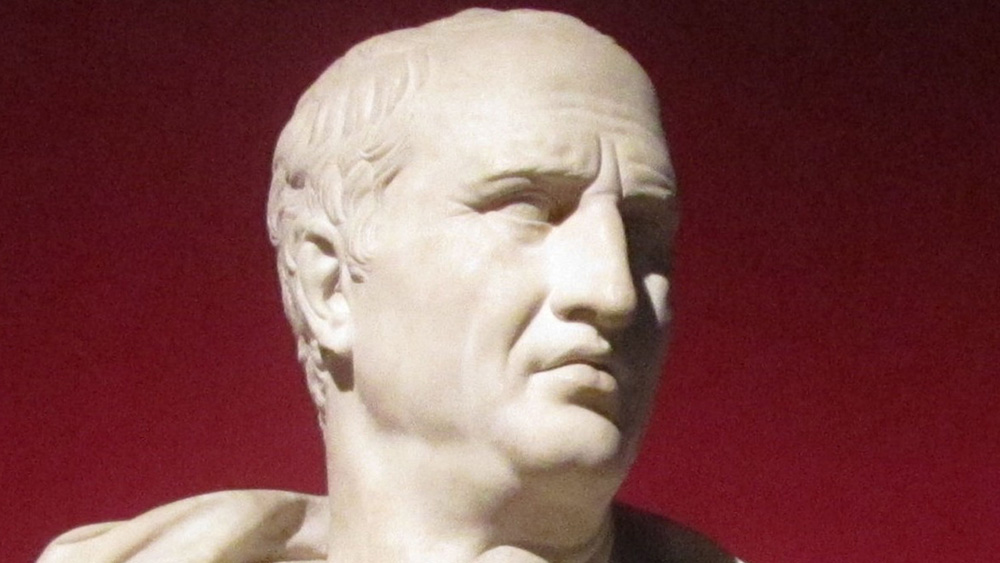

He was stirringly eloquent, silver-tongued and sharp-witted. He was a statesman who delivered rousing speeches and foiled a coup d’état against the Roman Empire. He was a natural-born politician to whom rising to offices of state seemed to come easily. Revered as the “father of the fatherland”, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 BC) was a great champion and defender of the Roman Republic in the first century before Christ. He saw in his day with growing concern how the state under Gaius Julius Caesar was moving toward a military dictatorship. His outspoken opposition to Caesar’s successor, Marcus Antonius, ultimately became his undoing. Proscribed for assassination by Marcus Antonius, history records that Cicero, while on the road fleeing for his life, leaned his head out of his litter and was swiftly beheaded. The henchmen also cut off his hands. They nailed his severed hands along with his head to the same rostrum in the Forum where he had once been cheered frenetically by the masses.

No historians doubt Cicero’s significance in his day as a politician and thinker. But that was two thousand years ago. The question that occupied him back then – What causes the downfall of great republics? – has not lost any of its immediacy to this day. But do the writings of the Roman philosopher and statesman contain answers to it that are still pertinent in the current age? What would Cicero have to say about the impeachment process in the United States and especially about Donald Trump?

Quite a lot, asserts historian Benjamin Straumann with conviction. The European Research Council (ERC) seems to share his opinion: It just awarded a grant of almost EUR 2 million to the scholar, who teaches and conducts research at the University of Zurich and at New York University. This ERC Consolidator Grant will enable Straumann and his team to explore a variety of questions about Cicero, such as: How have the theories put forth by the Roman philosopher evolved over the last two millennia? How has Cicero shaped our conception of justice? In Straumann’s view, these questions definitely have to do with the here and the now: “We need a long historiography of thought that illuminates the great turning points of history and helps to explain our contemporary world.”

One such turning point was the founding of the United States of America. The country’s founding fathers entered completely uncharted territory in the late 18th century, when they resolved to establish their new state as a republic. The world around them consisted almost exclusively of monarchies. But a king was out of the question for the colonists, who had just wrested their independence from the British crown. A few republics existed at that time – the cantons of Switzerland ranked among them, as did the Dutch provinces and the Republic of Venice – but they were all small, readily manageable entities. None of them had a land area even remotely as large as that of the new confederation of states in North America.

That’s why in their search for a model to follow, America’s founding fathers had to journey far back in history – all the way to the Roman Empire, for only the Romans had once endeavored to give a vast state a republican structure, and it was vital now to learn from their experiences.

“Historiography had long proceeded on the assumption that the Americans in those days were primarily inspired by the Roman ideal of civic virtue,” says Straumann, which means that for a republic to work, citizens must put the commonweal ahead of their own personal interests. Many thus viewed the collapse of the Roman state as resulting from moral decay.

Straumann sees it differently. He believes that the Americans mainly took their bearings from Cicero, who had an entirely different answer to the question of how Caesar was able to turn a great republican empire into a military dictatorship. “According to Cicero, what the Romans lacked to preserve the republic wasn’t civic virtue,” says Straumann, “but rather a constitution, because in the Roman statesman’s judgment, laws alone are insufficient to maintain a stable republic. What’s also needed are certain irrevocable principles and norms of justice above those laws, a constitution that antecedes popular sovereignty and liberty and delineates their bounds.”

Cicero in his day was unable to prevent the fall of the Roman Republic. But the founding fathers of the United States drew lessons from his writings. They gave the United States of America a constitution. It was passed in 1787 and originally consisted of seven articles. Now, for the first time in history, the edifice of a large state had been erected on the foundation of an explicit written legislative text. A political order with core elements such as constitutionally guaranteed rights and a separation of powers between a president, a bicameral congress and an independent judiciary had been set up to ward off future gravediggers of the republic.

And in fact, the US Constitution has thus far outlasted no less than 44 presidents. But will it also withstand the assaults on it by Donald Trump, a head of state who evidently is invulnerable even to charges of felonious abuse of office? “The actions of the sitting president are of course chipping away at the legal order,” says Straumann, who is a privatdozent teaching ancient history at the University of Zurich. He adds, though, that President Trump, with his attempt for instance to withhold aid from the government of Ukraine to coerce it to help his election campaign, is far from the first head of state to undermine the US political order. The limits of executive power have been stretched again and again throughout history. Straumann cites the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II and the denial of due process to the prisoners in the detention camp in Guantanamo Bay during the George W. Bush presidency as examples.

“Fears of a president shattering the political foundations of the United States like Caesar did to the Roman Republic are as old as the US Constitution itself,” says Straumann. He explains, however, that the founding fathers deliberately granted presidents wide-reaching decision-making autonomy during times of emergency; here, too, they had learned from the fall of the Roman state and from Cicero’s conclusions. “Where a president enjoys the liberties of a dictator, he does so with the Constitution’s blessing.”

Over the longer run, though, that power is subject to numerous checks and balances. And by no means does every response to a crisis stand up to later scrutiny and actually prove to be constitutional. But even if it’s determined in hindsight that the executive branch grossly overstepped its authority, “that’s little consolation for the victims of such grave abuses,” the historian points out. “The injustice done to them often cannot be rectified.”

Nevertheless, this capacity to self-correct is one of the great strengths of the US Constitution to this day, believes Straumann. This self-corrective capacity causes the legal order to periodically get sounded out anew, prevents its principles from getting forgotten, and keeps it relevant and in step with the times. Moreover, he adds, the conception of justice shaped by Cicero also raises an objection to the moral skepticism of our day – the idea that there is no such thing as objective justice. According to the Roman philosopher and statesman, it is indeed possible to justify and enshrine certain minimum objective norms to safeguard the stability of a republic.

And so, the 45th president, too, is unlikely to cause the political foundations of the United States to crumble. “A federal constitution that survived Richard Nixon and even a civil war will arguably also withstand a Donald Trump presidency,” the scholar says. Straumann believes that the real danger lurks elsewhere: “If the federal constitution should someday become a meaningless document to most Americans, the stability of the state will then truly be at risk.”