Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

The pancreatic islets of Langerhans play a key role when it comes to regulating how the body metabolizes sugar. The β cells located there monitor the blood sugar levels and secrete insulin as required. Insulin in turn triggers the uptake of sugar into cells. In patients suffering from type 1 diabetes, these β cells are attacked and destroyed by the body’s own white blood cells.

Little is known about what happens inside of the pancreas when diabetes develops, since performing biopsies or high resolution imaging of the organ is not feasible when patients are alive. “Much of what we know about type 1 diabetes in humans is based on pancreases from organ donors, and these are very rare,” says Bernd Bodenmiller from the Institute of Quantitative Biomedicine of the University of Zurich. This is why researchers are keen to gain as many insights as possible from every single organ that is donated.

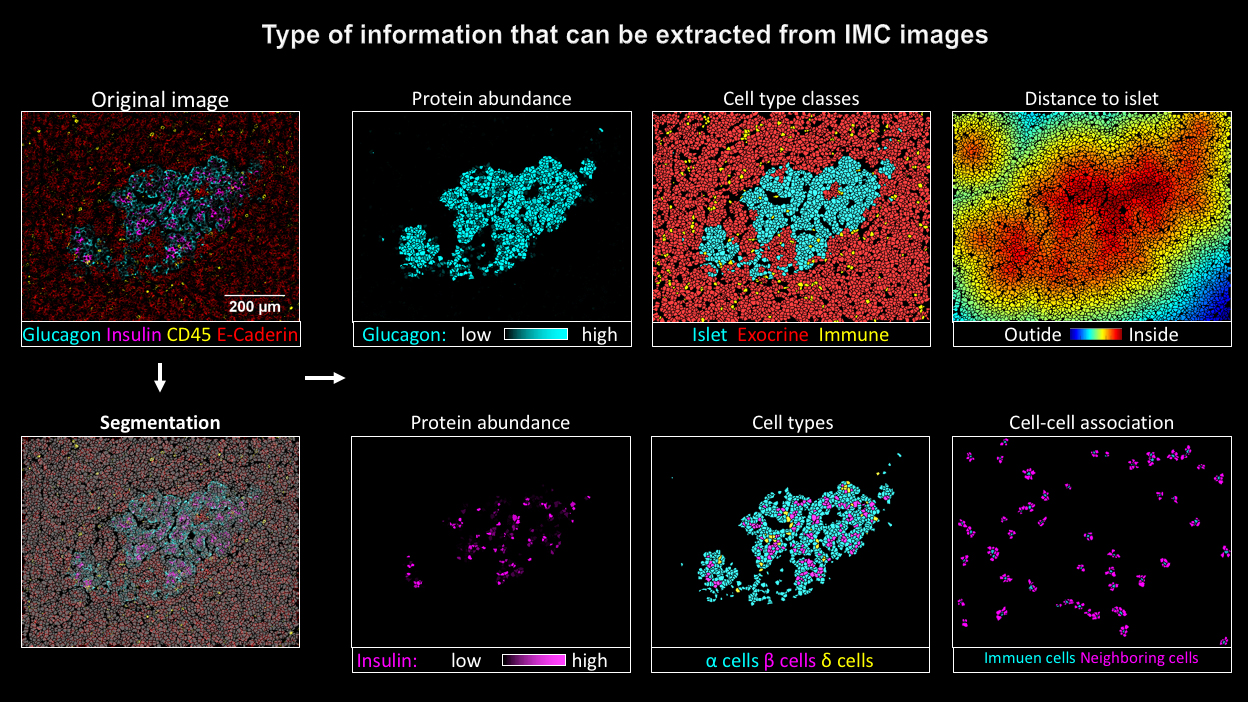

Bodenmiller and his team, working together with research groups in Geneva and in the US, have now for the first time used imaging mass cytometry to investigate donated pancreases: “This allows us to visualize β cells, other types of cells in the Langerhans islets as well as invading immune cells at the same time,” says Bodenmiller about the advantages of the method, which was developed under the lead of the University of Zurich. “This has previously not been possible using traditional approaches.”

For their study Nicolas Damond, first author of the publication from the Institute of Quantitative Biomedicine, analyzed 12 donated pancreases – four from healthy donors, four from patients in the early stages of type 1 diabetes and four from patients with advanced type 1 diabetes. The scientists used the findings to develop a map that shows the location of the different cell types in the pancreatic islets and the state the β cells were in.

Damond then compiled the data from the various donated organs in a pseudo timeline. This allowed him to reconstruct the changes in the pancreatic tissue from the onset of type 1 diabetes right up to the final stages of the disease.

One of the findings was particularly interesting: There was still a surprisingly high number of β cells in the pancreatic islets of Langerhans during the disease’s early stages. These cells might look different and produce less insulin than healthy cells, but they could possibly still be saved from complete destruction. “If we succeed in stopping the autoimmune attack this early, the cells could maybe regain their function and help with regulating the blood sugar levels of patients,” says Damond.

Through imaging mass cytometry the research group also located the special type of white blood cells which, according to current scientific knowledge, are responsible for β cell destruction. The researchers found these immune cells mainly in the pancreases of patients in early stages of the disease, especially in pancreatic islets that contained a high number of surviving β cells. Pancreatic islets whose β cells had been mostly destroyed, in contrast, had fewer white blood cells.

These results could help to shed light on the mechanism of the autoimmune reaction, about which there are currently still many open questions. “Our study demonstrates that imaging mass cytometry can make a valuable contribution to a better understanding of how type 1 diabetes progresses. It provides a basis for planning further experiments and developing new hypotheses,” believes Bodenmiller.

Nicolas Damond, Stefanie Engler, Vito R.T. Zanotelli, Denis Schapiro, Clive H. Wasserfall, Irina Kusmartseva, Harry S. Nick, Fabrizio Thorel, Pedro L. Herrera, Mark A. Atkinson, and Bernd Bodenmiller. A Map of Human Type 1 Diabetes Progression by Imaging Mass Cytometry. Cell Metabolism, 31 January 2019. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.11.014