Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

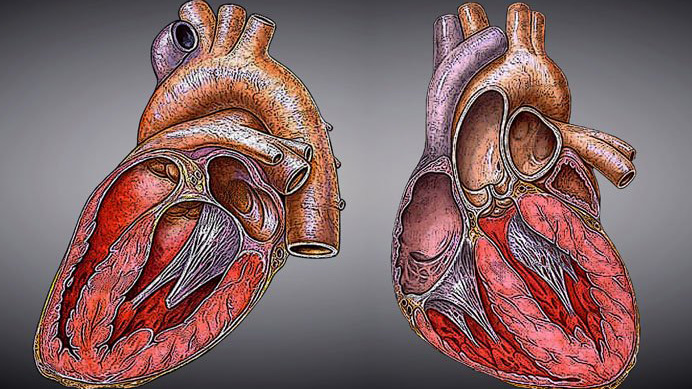

In 1967 it caused a sensation: When doctor Christiaan Barnard implanted a new heart into a man in South Africa, he achieved the hitherto unimaginable. However, despite the successful operation, the patient died 18 days later of a lung infection. Since then, heart surgery has made massive progress: Nowadays more than 90 percent of patients survive a transplant and in general go on to enjoy very good quality of life. The procedure means people who were terminally ill due to a weak heart are able to live normal lives again.

“From a purely technical point of view, heart transplants today are relatively straightforward operations in which large arteries are joined together,” said Michele Genoni, professor of heart surgery at UZH and head of the heart surgery department at Triemli Hospital. Even if organ transplants are today widely accepted in society, they still pose many medical challenges: Alongside possible infections, there is a risk that the body rejects the organ, as well as potential side effects from medication. Above all, however, a transplant always also has a psychological effect.

Living with a stranger’s heart

The question of whether it was ethical to remove the heart of a person who was brain dead was asked even in the earliest days of heart transplants. According to Genoni, an organ transplant is always a difficult and emotional affair, both for the family of the deceased donor, and for the surgeons and the recipient of the organ. In his lecture, Genoni gave a vivid impression of how radically a heart transplant changes the lives of patients.

It can even result in personality changes, said Genoni. One of the reasons for this is that before the operation, some heart patients have been waiting years for a new heart. During this time, the patients require help with daily life and have the shadow of death hanging over them constantly. Some of them die before a suitable donor heart is found. The patients spend a long time living with anxiety and insecurity. Then they suddenly get the call from the hospital, and the operation takes place only a few hours later. “After the transplant, the patients feel overwhelmed and happy that they have survived and that they can live normal lives again,” said Genoni. Without exception, they are incredibly grateful for the gift they have been given.

But there are also downsides. Their everyday lives change drastically – the patients can now look after themselves again, and are no longer dependent on the help of others, for example their partners. A positive change, of course, but one which can be challenging for relationship dynamics. And an aspect which is not to be overlooked is having to come to terms with having a foreign organ inside your body, something many patients struggle with. “The recipients feel the new heart beating. But they feel a heart beating that is not their own,” said Genoni, “and they know they owe their life to the death of another person.” People dealing with such a problematic situation require close psychological support.

Artificial hearts as alternatives

A future alternative to transplants could be offered by artificial hearts. Artificial hearts have already been in use for many years as a temporary solution while patients are waiting for a donor heart. They consist of a mechanical pump that is connected to the real heart in order to improve its performance. The artificial heart is connected with a cable to an external energy source.

Although artificial hearts as temporary solutions can be lifesaving and increase quality of life, they carry many associated risks. The blood in the donor hearts tends to clot, for example, which can lead to strokes and embolisms. There is also considerable risk of infection, mainly due to the exit holes below the navel for the cables. With such disadvantages, an artificial heart cannot yet be considered as a long-term alternative to a donor heart. But many researchers are working on improving the technology. The large interdisciplinary project “Zurich Heart” aims to improve the technology enough so that, for example, an energy supply without an external connection would be possible.

This would considerably increase quality of life and above all reduce the risk of infection. In addition, the artificial heart of the future should be able to adapt itself automatically to the individual physical performance of the patient and should no longer cause blood clots thanks to improved materials. There is still a long way to go, but progress so far is very promising.