Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

Professor Schaepman, you were at the control center in Darmstadt to follow the launch of the Vega rocket in French Guiana. It was transporting “your” satellite into space. What went through your mind during the launch?

Michael Schaepman: We’ve been working towards this moment for the last five years, so naturally we’re very excited. The project has now entered the decisive phase, and the Sentinel-2A satellite will soon be delivering the first mapping data – thanks in part to our input.

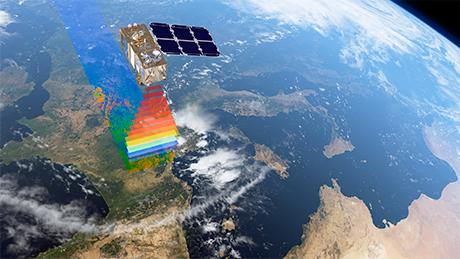

At the heart of the Sentinel-2A is a multispectral imager (MSI) that maps vegetation on the earth from an altitude of around 800 kilometers. What crucial contribution did you and your team made to the MSI?

Michael Schaepman: We co-developed the specifications to enable the MSI to monitor the planet’s vegetation and changes in it at high resolution. The instrument delivers multi-spectral data with 13 bands in the visible, near infrared, and short-wave infrared part of the spectrum. Thanks to our know-how, the imager on board the satellite can supply data that reliably map changes in vegetation.

What does the satellite monitor?

Michael Schaepman: Sentinel-2A focuses on land vegetation. In addition to forests, agricultural areas, and grasslands, the MSI maps bodies of water, roads and buildings, and the impact of natural disasters such as volcanic eruptions. The satellite has a frequent revisit cycle: With the launch of the second Sentinel-2B in 2016, the entire surface of the earth will be mapped every five days. This means it will be possible to monitor even short-term changes, allowing us to map the development of plant health or the growth of forests – in other words, changes in land cover and vegetation. This will enable countless potential uses and practical applications.

Can you give examples?

The Sentinel-2A satellite project, part of the European Commission’s Copernicus earth monitoring program, involves many groups pursuing many different projects. From our perspective within the UZH Global Change and Biodiversity University Research Priority Program (URPP), we’re particularly interested in changes in vegetation, in other words, biodiversity and how it influences the way an ecosystem functions. Thanks to the satellite we’ll be able to map changes in biodiversity on a large scale, first of all in the six experimental systems we’re investigating (Siberia, the Tibetan plateau, Lake Zurich, Lägern, Aldabra, and Borneo), and then in entire ecosystems (temperate forests, rainforests, tundra, alpine grasslands, and subtropical atolls).

We’re also interested in photosynthetic activity in the vegetation as a source of insights into plant growth and health. By mapping photosynthetic activity we’ll also be able to find out how vegetation is responding to the most important components of global change and climate warming, for example chemical pollution, invasive plant species, and changes in land use.

When will you get the first data from Sentinel-2A?

Michael Schaepman: We expect the first data in three months. Evaluation will take a while longer. We should be able to do the first analysis around six months from now.

What’s next?

Michael Schaepman: The Sentinel program always involves two identical satellites. As I already mentioned, once Sentinel-2A is successfully established, Sentinel-2B will be launched. The two Sentinels are configured to optimally coordinate the timing of the imaging they provide. So it will continue to be very exciting.