Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

In 2010 Milas, a sleepy rural town in southwest Turkey, became the site of an important find when a tomb of archeological significance dating from the fourth century BC was discovered in a town house with ancient foundations. The burial chamber was decorated with colorful wall paintings, and the marble sarcophagus was adorned with reliefs depicting hunting and family scenes.

There are very few meaningful artifacts extant from the 4th century BC. At that time the southwest coast of modern-day Turkey was ruled by Carian satrap Mausolus under the hegemony of Persia. Although he supported the native Anatolian Carian culture, Mausolus was also a patron of Greek art and literature.

Around 367 BC he moved the capital of Caria from Milas to the port of Halicarnassus – now Bodrum, an important tourist destination – where he had Greek master-builders and artists erect splendid buildings. He also commissioned a tomb for himself, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus. To this day the mausoleum has been regarded as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

“The whole style of the tomb in Milas is reminiscent of the famous mausoleum at Halicarnassus,” says Professor Christian Marek, an expert in ancient history at the University of Zurich. Following the discovery of the Milas tomb in 2010, Marek was the specialist commissioned by the Turkish government to study the inscriptions on the site.

Marek’s research in Turkey goes back thirty years. He’s an expert in the history and culture of Asia Minor and the ancient history of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East region. Since the first half of the 1980s he has also been conducting field research and epigraphic studies in Asia Minor.

Now, four years after the unearthing of the tomb in Milas, Marek has made a further discovery. Turkish archeologists had uncovered a number of late antique houses that must have been erected at a time after the tomb was built. “There I noticed a staircase that apparently belonged to the houses. On the steps I could make out classical Greek characters,” says Marek. “Shortly after that the stairs were excavated, and we had before us a long stela with 124 lines of poetry carved into it.”

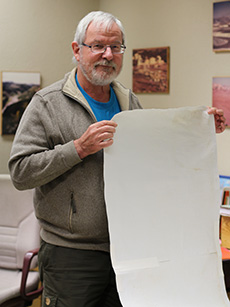

Marek quickly had the feeling he had found something astonishing. He was right. The inscription is the longest extant Greek poem found carved in stone, and is unique in terms of the language and type of verse used. Unfortunately part of the poem can no longer be made out because the carved text has been worn away from the step. The historian immediately made a so-called squeeze by wetting a thick piece of paper and pressing it onto the inscription to make an imprint.

At the moment Marek is in Zurich, working with his team to decipher and translate the inscription. What they know so far: “It’s a poem describing the life and work of a man called Pytheas, and the battles he fought. Pytheas was the name of the famous architect of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus,” explains Marek, conjecturing that the Pytheas of the inscription and the architect could be one and the same person.

The poem recounts the life of a very busy man in poetic language written in trochaic tetrameter. At the time this was a popular meter for verse, which could also be sung to the accompaniment of a flute. The real challenge for Marek and his team now is to fill in as many of the missing parts as possible and interpret the text. The plan is to publishing the findings of their research in a book at the end of 2015. One thing is already certain: In the future Marek’s insights will serve as a basis for many more researchers to work on this extraordinary find to gain a deeper understanding of the age of the Persians and ancient Greeks.